How the Potomac shaped our society and economy

/Home to the nation’s capital, the Potomac River is permanently interwoven with the country’s foundations

photo courtesy of konstantin’s europe and more via flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The Potomac River region’s abundant natural resources have helped support its residents for centuries. Home to the nation’s capital, the river inevitably became a political landmark and a vital part of the local—and national—economy.

Early economy and politics

Native Americans called the river “the place where people trade,” and it was heavily traveled by Native peoples to trade goods.

They also found nourishment in the river’s abundant fish populations, developing efficient methods to capture fish. One method involved using a large basket, which was useful for harvesting a small amount of fish and feeding one family.

Another, more fruitful method was creating large fish traps in the river itself. These traps were enclosures that had one opening for fish to enter. Where the river has a soft, muddy bottom, Native people built traps with tall reeds or sticks, which were quick to make but had a short lifespan due to their existence in an ever-flowing river.

Where the Potomac has a stony floor, however, they made similar traps with rock. Fish flowed into large V-shaped weirs of piled-up stone and could not escape, making these constructions invaluable to tribes. Some of these rocky structures can still be seen in the river today!

When the first colonists came to America, they struggled with farming on the unfamiliar soil, but they quickly saw the value of the river’s fish. They applied European fishing techniques to capture herring and shad, including similar enclosures of wooden stakes, weirs, and nets that Native people used.

Before long, though, colonizers took Virginian lands and made them into tobacco farms. Before the Revolutionary War, port towns were developed to assist with the farms so the cash crop could be shipped overseas. Indentured servants handled the brunt of the work.

Although tobacco was a labor-intensive crop, the business was so successful that tobacco quickly became the basis of Virginia’s economy. Notes payable by tobacco could be used to make purchases.

tobacco plant. photo courtesy of David Hoffman via flickr (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Robert Peter, who lived in what is now Montgomery County, Maryland, was one of the most successful tobacco moguls in the mid 1700s, establishing weighing stations and warehouses all along the Potomac River to trade tobacco. One of these trade centers was in Georgetown, making it a popular trade city that would later become part of the District of Columbia.

Tobacco didn’t come without a cost though—the business cleared acres of forested land, and tons of harmful sediment entered the Potomac. Tobacco also rapidly drains soil of nutrients, and attempts to re-grow the crop on the same land would eventually give poor yields, driving the desire for new land and leading to more deforestation.

With the constant need for fresh land, the business model was not sustainable. The General Assembly passed a law in 1632 reducing the number of plants each Jamestown settler could grow, though this just made the settlers look farther for untouched land. The production of tobacco continued to be a popular and profitable business until around 1775, when the Revolutionary War began.

The goal was to stop sending Britain tobacco and to switch to another crop that would better serve American troops: wheat.

In particular, the Shenandoah Valley became a hot spot for wheat, and the towns of Norfolk, Richmond, and Alexandria became crucial in exporting the crop in the 1800s. Today, wheat is still grown in Virginia, making up part of the approximately $70 billion and 334,000 jobs that the state’s agriculture industry contributes to the economy.

Washington’s vision

George Washington was born in the Potomac River region, and its rich ecology attracted the first president to make his home there. He secured a spot near the river to become the nation’s capital as part of the Compromise of 1790, where it was decided the government would assume state debts in exchange for building the nation’s capital near Washington’s house in Mount Vernon after a ten-year stay in Philadelphia.

During those ten years, political parties became more defined, and Washington, DC, was born out of the Potomac.

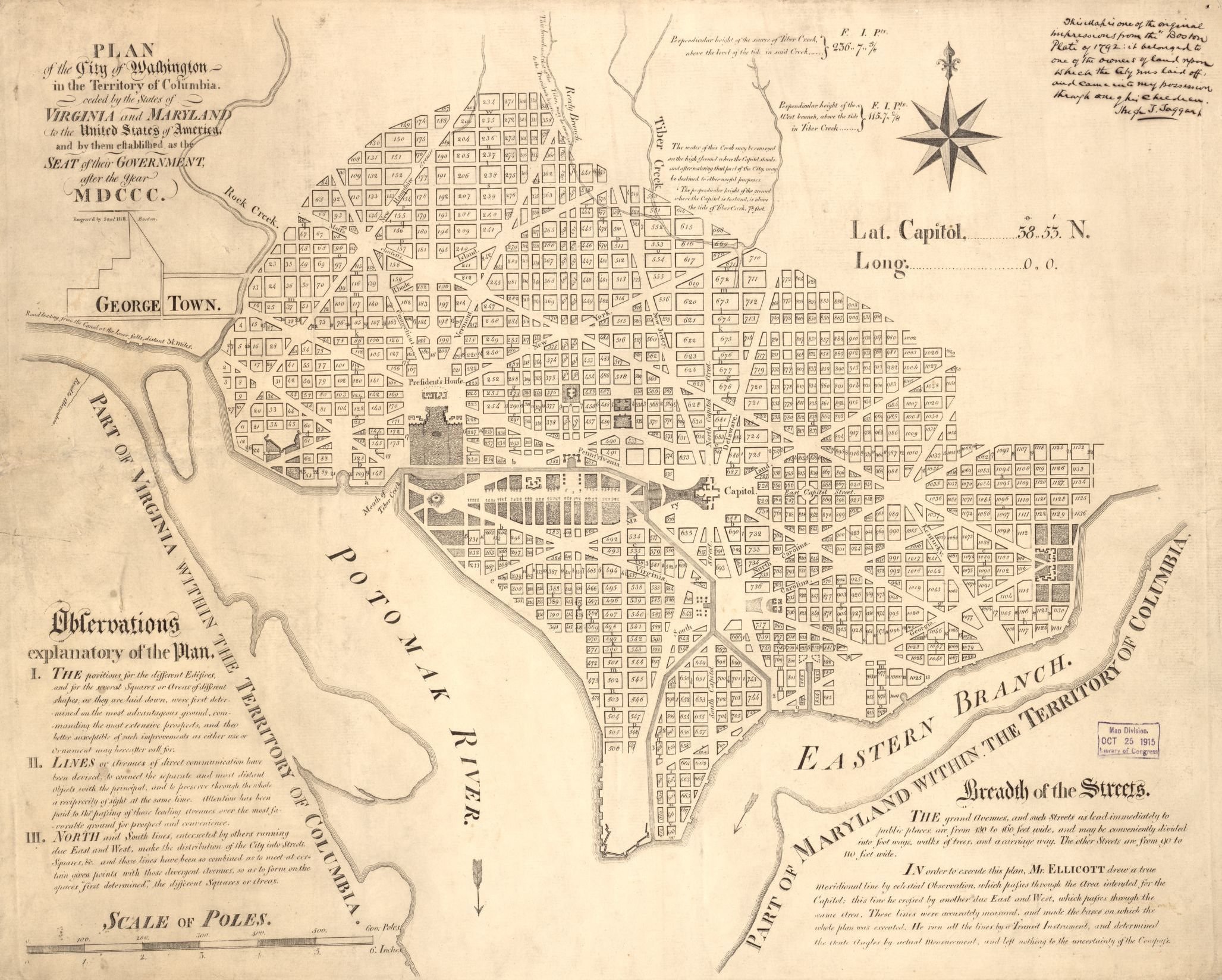

photo courtesy of Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

Meanwhile, Washington saw the opportunity for the river to become a highway to the West, and instigated the construction of canals to drive trade.

While the canals ultimately became defunct, railways along the river followed similar routes, the river guiding trade to other parts of the nation. The first commercial railroad in America, the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad opened in 1830 and operated entirely in Maryland for several years until its line extended across the Potomac River into Virginia in 1837.

The booming fishing business

salt house at mt. vernon. photo courtesy of Tim Evanson via flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Washington also worked to create a fishing empire as the river teemed with fish, herring, shad, and sturgeon. Determined to glean wealth from the Potomac, Washington established three fisheries along Mount Vernon, which contained roughly ten miles of river and 8,000 acres of land. Enslaved people harvested and gutted fish before salting, packing, and shipping them.

Because millions of herring and shad were brought in during each spring, salt was needed to preserve the fish—a lot of it.

Salt was imported from Lisbon, Portugal, where the mineral was created by flooding areas with saltwater and allowing the water to slowly evaporate. This process left salt more durable and slower to dissolve.

However, Lisbon salt was not so easy to come by in the colonies, nor was it affordable. Because of English law, ships containing the salt would have to first sail to England to pass customs and pay duties before coming to the colonies, and often had to arrive at a northern colony before being able to enter Virginia.

English salt from Liverpool was less hardy but cheap. Not nearly as effective as Lisbon salt, it only preserved fish for 6 to 8 months.

Any leftover fish remains would be applied to Washington’s farmlands as a nutritious fertilizer. While his most profitable enterprise was fishing, Washington also grew wheat and other foods on his estate.

Salt proved to be extremely effective at preserving fish—in 1991, an archaeological team unveiled a barrel of salted herring on a sunken ship from 1830 and found it was still safe to eat!

The rise of coal towns

Coal mining had begun as early as 1810, in a town called Wheeling (in what is now West Virginia). The C&O Canal, and soon the B&O and other railroads, were used to transport the coal. After the Civil War, more and more mines popped up along the North Branch of the Potomac.

Towns were built specifically for mining, and during the height of the industry in the 1900s, Maryland mines produced roughly 5 million tons of coal annually.

While profitable, the mines had major consequences for the Potomac and other rivers. Acid mine drainage caused heavy metals like lead, mercury, and copper to be released into rivers. High levels of these metals drastically reduced water quality and killed fish and native plants.

Mines could also be abandoned without any cleanup or preventive measures, leaving dangerous sites and pollutants that inevitably entered waterways. No regulations existed until 1977, when Congress passed the Federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act.

Abandoned coal mine in Garrett County, Maryland. Photo by Arthur Rothstein.

Presidential connections

Aside from living in the river’s vicinity, many presidents have other special ties to the Potomac.

The White House’s location, less than a mile away from where Tiber Creek enters the Potomac, was swampy and buggy. Mosquitoes carrying disease were prevalent, the Washington Canal was built nearby, and humid summers made it even easier for illness to spread. All of these factors adversely affected future presidents’ health.

Of course, the Potomac still had nice areas. John Quincy Adams enjoyed a refreshing, early morning swim in the river. Allegedly, one morning, his clothes got swept up in the wind and he had to sneak back to the White House unnoticed.

Modern economy and politics

While it may not compare to the river Washington fished in, the modern commercial fishing industry still proves to be profitable, particularly with oysters, blue crabs, and rockfish. However, declining water quality led to smaller populations of these animals and a dip in profits.

In addition to shad and herring, sturgeon was one of the more prized fish. Both the fish and their eggs were harvested and sold. Eventually, pollution and overharvesting nearly wiped out this fish entirely from the Potomac River, with commercial fishing of sturgeon ending in the 1920s.

While they are still a rare sight, some lucky anglers have reported seeing the fish in recent years, a hopeful sign that the health of the river is improving.

Two species of sturgeon have been known to live in the Chesapeake: the shortnose sturgeon and the Atlantic sturgeon, also known as the “King of Fishes.” Atlantic sturgeon can grow as long as 16 feet, weigh up to 800 pounds, and live for 60 years!

Faced with increasing pollution, plummeting fish populations, and public health concerns, the government began to implement policies and laws to protect the river.

sturgeon. photo courtesy of Aileen Devlin / Virginia Sea Grant via flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0)

In 1940, Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and the District of Columbia created the Interstate Commission of the Potomac River Basin. Individual states also started monitoring their own water quality.

The Water Quality Act of 1965 established a Federal Water Pollution Control Agency, requiring standards of water quality. Several years later, the Clean Air Act mandated emission control from power plants. Finally, the Clean Water Act of 1972 paved the way for the river’s recovery.

Without these protections, the river would likely not be healthy enough to provide a setting for recreational activities, which make up a large portion of the river’s economy today. Maryland’s recreational boating generated approximately $2 billion in one year.

The Potomac’s true value, though, is that it has something to offer to everyone. Casual and professional athletes (even fishermen) enjoy the river as the opportune spot to practice their sport—did you know Olympic athletes train on the Potomac? Its waters are perfect training spots for canoers and kayakers! Cyclers, runners, and walkers trek throughout the many scenic parks and trails alongside the river, and can stop to rest and take in the beautiful scenery. Its rich and diverse ecosystem makes birdwatchers flock to its waters.

photo by potomac conservancy

If nothing else, the river provides a constant in a world that is constantly changing. Sustainability is key for maintaining that constant, and there have been strides to build a sustainable economy around the Potomac River.

While gas and coal prevailed as the region’s power source in the past, renewable energy (such as water and solar) have become more integrated into the electricity infrastructure. Projects such as the District Wharf, green roofs on city buildings, and improvements in waterfront areas all contribute economically while protecting the river.

For centuries, the Potomac River served as the nation’s backbone and the basis for the local economy. The political and economic significance of the river still reigns true today, though in different ways. Advocating for clean water and working to mitigate the effects of the climate crisis will provide more opportunities for the country’s economy and politics to evolve.